API architecture refers to the set of rules, protocols, and tools that dictate how software components should interact. The architecture of an API is not just about facilitating communication; it’s also about ensuring that this communication is efficient, secure, and scalable. https://hackernoon.com/the-system-design-cheat-sheet-api-styles-rest-graphql-websocket-webhook-rpcgrpc-soap

A well-designed API architecture can significantly enhance the performance of a system, while a poorly designed one can lead to bottlenecks, security vulnerabilities, and maintenance nightmares.

Different Styles of API Architecture

The most common API design styles:

-

REST (Representational State Transfer) is the most used style that uses standard methods and HTTP protocols. It’s based on principles like statelessness, client-server architecture, and cacheability. It’s often used between front-end clients and back-end services.

-

GraphQL is a query language for APIs. Unlike REST, which exposes a fixed set of endpoints for each resource, GraphQL allows clients to request exactly the data they need, reducing over-fetching.

-

WebSocket is a protocol allowing two-way communication over TCP. Clients use web sockets to get real-time updates from back-end systems.

-

Webhook is a mechanism that allows one system to notify another system about specific events in real-time. It is a user-defined HTTP callback.

-

RPC (gRPC) is a protocol that one service can use to request a procedure/method from a service located on another computer in a network. Usually, It’s designed for low-latency, high-speed communication.

-

SOAP is a protocol for exchanging structured information to implement web services. It relies on XML and is known for its robustness and security features, currently considered a legacy protocol.

Let’s look at each protocol separately with all their pros, cons, and use cases.

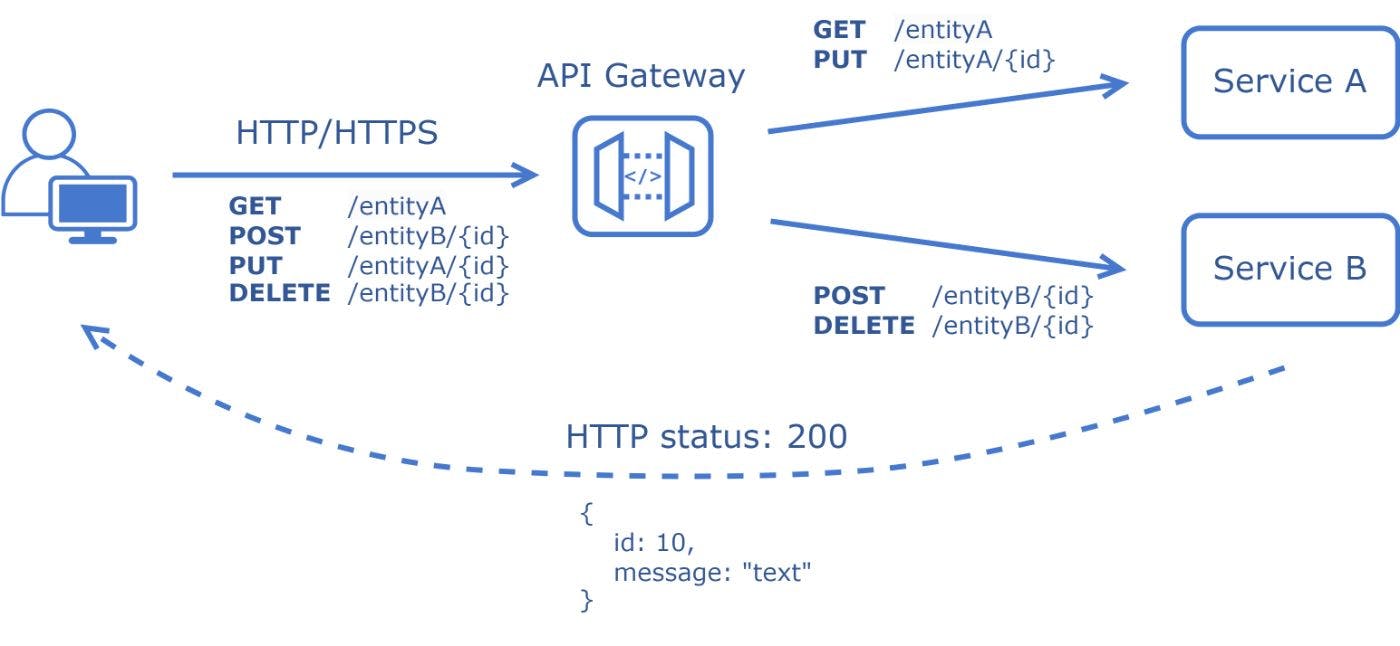

REST

REST is an architectural style that uses standard conventions and protocols, making it easy to understand and implement. Its stateless nature and use of standard HTTP methods make it a popular choice for building web-based APIs.

While REST has been the de facto standard for building APIs for a long time, other styles like GraphQL have emerged, offering different paradigms for querying and manipulating data.

Format: XML, JSON, HTML, plain text Transport protocol: HTTP/HTTPS

Key Concepts and Characteristics

- Resource: In REST, everything is a resource. A resource is an object with a type, associated data, relationships to other resources, and a set of methods that operate on it. Resources are identified by their URIs (typically a URL).

- CRUD Operations: REST services often map directly to CRUD (Create, Read, Update, Delete) operations on resources.

- HTTP Methods: REST systems use standard HTTP methods:

- GET: Retrieve a resource.

- POST: Create a new resource.

- PUT/PATCH: Update an existing resource.

- DELETE: Remove a resource.

-

Status Codes: REST APIs use standard HTTP status codes to indicate the success or failure of an API request:

- 2xx - Acknowledge and Success

- 200 - OK

- 201 - Created

- 202 - Accepted

- 3xx - Redirection

- 301 - Moved Permanently

- 302 - Found

- 303 - See Other

- 4xx - Client Error

- 400 - Bad Request

- 401 - Unauthorized

- 403 - Forbidden

- 404 - Not Found

- 405 - Method Not Allowed

- 5xx - Server Error

- 500 - Internal Server Error

- 501 - Not Implemented

- 502 - Bad Gateway

- 503 - Service Unavailable

- 504 - Gateway Timeout

- 2xx - Acknowledge and Success

-

Stateless: Each request from a client to a server must contain all the information needed to understand and process the request. The server should not store anything about the client’s state between requests.

-

Client-Server: REST is based on the client-server model. The client is responsible for the user interface and experience, while the server is responsible for processing requests, handling business logic, and storing data.

-

Cacheable: Responses from the server can be cached by the client. The server must indicate whether a response is cacheable or not.

-

Layered System: A client cannot ordinarily tell whether it is connected directly to the end server or an intermediary. Intermediary servers can improve system scalability by enabling load balancing and providing shared caches.

- HATEOAS: Hypermedia As The Engine Of Application Stat is a REST web service principle that enables clients to interact with and navigate through a web application entirely based on the hypermedia provided dynamically by the server in its responses, promoting loose coupling and discoverability.

Use Cases

- Web Services: Many web services expose their functionality via REST APIs, allowing third-party developers to integrate and extend their services.

- Mobile Applications: Mobile apps often communicate with backend servers using REST APIs to fetch and send data.

- Single Page Applications (SPAs): SPAs use REST APIs to dynamically load content without requiring a full page refresh.

- Integration Between Systems: Systems within an organization can communicate and share data using REST APIs.

Example

- Request

GET “/user/42” - Response

{ "id": 42, "name": "Alex", "links": { "role": "/user/42/role" } }

GraphQL

GraphQL offers a more flexible, robust, and efficient approach to building APIs, especially in complex systems or when the frontend needs high flexibility. It shifts some of the responsibility from the server to the client, allowing the client to specify its data requirements.

While it’s not a replacement for REST in all scenarios, it offers a compelling alternative in many situations, particularly as applications become more networked and distributed.

Format: JSON

Transport protocol: HTTP/HTTPS

Key Concepts and Characteristics

-

Query Language for APIs: It allows clients to request the data they need, making it possible to get all required information in a single request.

-

Type System: GraphQL APIs are organized in terms of types and fields, not endpoints. It uses a strong type system to define the capabilities of an API. All the types exposed in an API are written down in a schema using the GraphQL Schema Definition Language (SDL).

-

Single Endpoint: Unlike REST, where you might have multiple endpoints for different resources, in GraphQL, you typically expose a single endpoint that expresses the complete set of capabilities of the service.

-

Resolvers: On the server side, resolvers gather the data described in a query.

-

Real-time Updates with Subscriptions: Beyond just querying data, GraphQL includes built-in support for real-time updates using subscriptions.

-

Introspective: A GraphQL server can be queried for the types it supports. This creates a strong contract between client and server, allowing for tooling and better validation.

Use Cases

-

Flexible Frontends: For applications (especially mobile) with crucial bandwidth, you want to minimize the data fetched from the server.

-

Aggregating Microservices: A GraphQL layer can be introduced to aggregate the data from these services into a unified API if you have multiple microservices.

-

Real-time Applications: With its subscription system, GraphQL can be an excellent fit for applications that need real-time data, like chat applications, live sports updates, etc.

-

Version-Free APIs: With REST, you often need to version your APIs once changes are introduced. With GraphQL, clients only request the data required, so adding new fields or types doesn’t create breaking changes.

Example

Request

GET “/graphql?query=user(id:42){ name role { id name } }”

Response

{

"data": {

"user": {

"id": 42,

"name": "Alex",

"role": {

"id": 1,

"name": "admin"

}

}

}

}

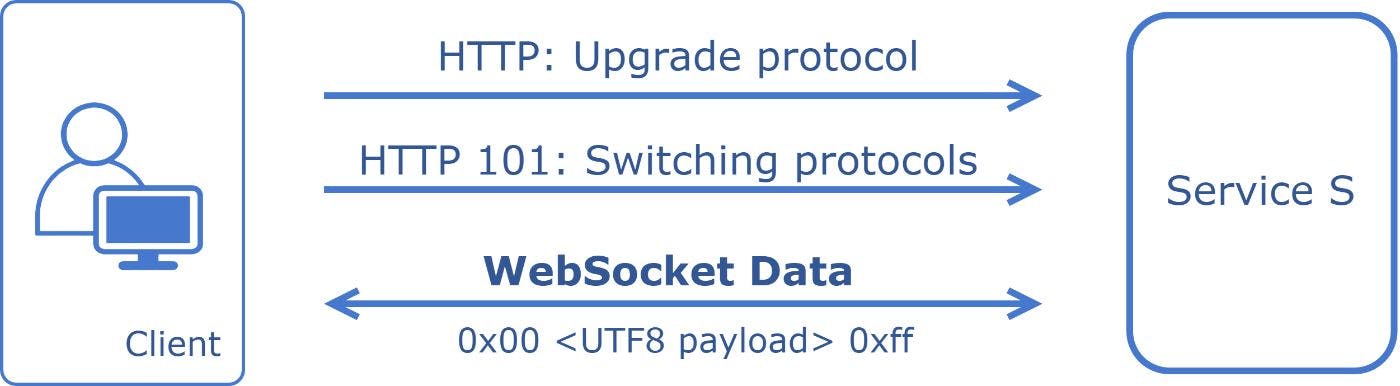

WebSocket

WebSockets provide a full-duplex communication channel over a single, long-lived connection, allowing real-time data exchange between a client and a server. This makes it ideal for interactive and high-performance web applications.

Format: Binary

Transport protocol: TCP

Key Concepts and Characteristics

-

Persistent Connection: Unlike the traditional request-response model, WebSockets provide a full-duplex communication channel that remains open, allowing for real-time data exchange.

-

Upgrade Handshake: WebSockets start as an HTTP request, which is then upgraded to a WebSocket connection if the server supports it. This is done via the

Upgradeheader. -

Frames: Once the connection is established, data is transmitted as frames. Both text and binary data can be sent through these frames.

-

Low Latency: WebSockets allow for direct communication between the client and server without the overhead of opening a new connection for each exchange. This results in faster data exchange.

-

Bidirectional: Both the client and server can send messages to each other independently.

-

Less Overhead: After the initial connection, data frames require fewer bytes to send, leading to less overhead and better performance than repeatedly establishing HTTP connections.

-

Protocols and Extensions: WebSockets support subprotocols and extensions, allowing for standardized and custom protocols on top of the base WebSocket protocol.

Use Cases

-

Online Gaming: Real-time multiplayer games where players’ actions must be immediately reflected to other players.

-

Collaborative Tools: Applications like Google Docs, where multiple users can edit a document simultaneously and see each other’s changes in real-time.

-

Financial Applications: Stock trading platforms where stock prices need to be updated in real-time.

-

Notifications: Any application where users need to receive real-time notifications, such as social media platforms or messaging apps.

-

Live Feeds: News websites or social media platforms where new posts or updates are streamed live to users.

Example

Request

GET “ws://site:8181”

Response

HTTP/1.1 101 Switching Protocols

Webhook

Webhook is a user-defined HTTP callback triggered by specific web application events, allowing real-time data updates and integrations between different systems.

Format: XML, JSON, plain text

Transport protocol: HTTP/HTTPS

Key Concepts and Characteristics

-

Event-Driven: Webhooks are typically used to denote that an event has occurred. Instead of requesting data at regular intervals, webhooks provide data as it happens, turning the traditional request-response model on its head.

-

Callback Mechanism: Webhooks are essentially a user-defined callback mechanism. When a specific event occurs, the source site makes an HTTP callback to the URI provided by the target site, which will then take a specific action.

-

Payload: When the webhook is triggered, the source site will send data (payload) to the target site. This data is typically in the form of JSON or XML.

-

Real-time: Webhooks allow applications to get real-time data, making them highly responsive.

-

Customizable: Users or developers can typically define what specific events they want to be notified about.

-

Security: Since webhooks involve making callbacks to user-defined HTTP endpoints, they can pose security challenges. It’s crucial to ensure that the endpoint is secure, the data is validated, and possibly encrypted.

Use Cases

-

Continuous Integration and Deployment (CI/CD): Triggering builds and deployments when code is pushed, or a pull request is merged.

-

Content Management Systems (CMS): Notifying downstream systems when content is updated, published, or deleted.

-

Payment Gateways: Informing e-commerce platforms about transaction outcomes, such as successful payments, failed transactions, or refunds.

-

Social Media Integrations: Receiving notifications about new posts, mentions, or other relevant events on social media platforms.

-

IoT (Internet of Things): Devices or sensors can trigger webhooks to notify other systems or services about specific events or data readings.

Example

Request

GET “https://external-site/webhooks?url=http://site/service-h/api&name=name”

Response

{

"webhook_id": 12

}

RPC and gRPC

RPC (Remote Procedure Call) is a protocol that allows a program to execute a procedure or subroutine in another address space, enabling seamless communication and data exchange between distributed systems.

gRPC (Google RPC) is a modern, open-source framework built on top of RPC that uses HTTP/2 for transport and Protocol Buffers as the interface description language, providing features like authentication, load balancing, and more to facilitate efficient and robust communication between microservices.

RPC

Format: JSON, XML, Protobuf, Thrift, FlatBuffers

Transport protocol: Various

#Key Concepts and Characteristics

-

Definition: RPC allows a program to cause a procedure (subroutine) to execute in another address space (commonly on another computer on a shared network). It’s like calling a function performed on a different machine than the caller’s.

-

Stubs: In the context of RPC, stubs are pieces of code generated by tools that allow local and remote procedure calls to appear the same. The client has a stub that looks like the remote procedure, and the server has a stub that unpacks arguments, calls the actual procedure, and then packs the results to send back.

-

Synchronous by default: Traditional RPC calls are blocking, meaning the client sends a request to the server and gets blocked waiting for a response from the server.

-

Language Neutral: Many RPC systems allow different client and server implementations to communicate regardless of the language they’re written in.

-

Tight Coupling: RPC often requires the client and server to know the procedure being called, its parameters, and its return type.

#Use Cases

-

Distributed Systems: RPC is commonly used in distributed systems where parts of a system are spread across different machines or networks but need to communicate as if they’re local.

-

Network File Systems: NFS (Network File System) is an example of RPCs performing file operations remotely.

#Example

Request

{ “method”: “addUser”, “params”: [ “Alex” ] }

Response

{

“id”: 42,

“name”: “Alex”,

“error”: null

}

gRPC

Format: Protobuf

Transport protocol: HTTP/2

#Key Concepts and Characteristics

-

Definition: gRPC is an open-source RPC framework developed by Google. It uses HTTP/2 for transport, Protocol Buffers (Protobuf) as the interface description language, and provides authentication, load balancing features, and more.

-

Protocol Buffers: This is a language-neutral, platform-neutral, extensible mechanism for serializing structured data. With gRPC, you define service methods and message types using Protobuf.

-

Performance: gRPC is designed for low latency and high throughput communication. HTTP/2 allows for multiplexing multiple calls over a single connection and reduces overhead.

-

Streaming: gRPC supports streaming requests and responses, allowing for more complex use cases like long-lived connections, real-time updates, etc.

-

Deadlines/Timeouts: gRPC allows clients to specify how long they will wait for an RPC to complete. The server can check this and decide whether to complete the operation or abort if it will likely take too long.

-

Pluggable: gRPC is designed to support pluggable authentication, load balancing, retries, etc.

-

Language Neutral: Like RPC, gRPC is language agnostic. However, with Protobuf and the gRPC tooling, generating client and server code in multiple languages is easy.

#Use Cases

-

Microservices: gRPC is commonly used in microservices architectures due to its performance characteristics and ability to define service contracts easily.

-

Real-time Applications: Given its support for streaming, gRPC is suitable for real-time applications where servers push data to clients in real-time.

-

Mobile Clients: gRPC’s performance benefits and streaming capabilities make it a good fit for mobile clients communicating with backend services.

#Example

message User {

int id = 1

string name = 2

}

service UserService {

rpc AddUser(User) returns (User);

}

SOAP

SOAP, which stands for Simple Object Access Protocol, is a protocol for exchanging structured information to implement web services in computer networks. It’s an XML-based protocol that allows programs running on disparate operating systems to communicate with each other.

Format: XML

Transport protocol: HTTP/HTTPS, JMS, SMTP, and more

Key Concepts and Characteristics

-

XML-Based: SOAP messages are formatted in XML and contain the following elements:

-

Envelope: The root element of a SOAP message that defines the XML document as a SOAP message.

-

Header: Contains any optional attributes of the message used in processing the message, either at an intermediary point or the ultimate end-point.

-

Body: Contains the XML data comprising the message being sent.

-

Fault: An optional Fault element that provides information about errors while processing the message.

-

Neutrality: SOAP can be used with any programming model and is not tied to a specific one.

-

Independence: It can run on any operating system and in any language.

-

Stateless: Each request from a client to a server must contain all the information needed to understand and process the request.

-

Built-in Error Handling: The Fault element in a SOAP message is used for error reporting.

- Standardized: Operates based on well-defined standards, including the SOAP specification itself, as well as related standards like WS-ReliableMessaging for ensuring message delivery, WS-Security for message security, and more. Use Cases

-

Enterprise Applications: SOAP is often used in enterprise settings due to its robustness, extensibility, and ability to traverse firewalls and proxies.

-

Web Services: Many web services, especially older ones, use SOAP. This includes services offered by major companies like Microsoft and IBM.

-

Financial Transactions: SOAP’s built-in security and extensibility make it a good choice for financial transactions, where data integrity and security are paramount.

- Telecommunications: Telecom companies might use SOAP for processes like billing, where different systems must communicate reliably. Example Request ~~~ xml <?xml version=”1.0”?>

Response

~~~ xml

<?xml version="1.0"?>

<soap:Envelope>

<soap:Body>

<m:AddUserResponse>

<m:Id>42</m:Id>

<m:Name>Alex</m:Name>

</m:AddUserResponse>

</soap:Body>

</soap:Envelope>

Conclusion

The landscape of API architecture styles is diverse, offering various approaches like REST, SOAP, RPC, and more, each with unique strengths and use cases, enabling developers to choose the most suitable paradigm for building scalable, efficient, and robust integrations between different software components and systems.