Author: Brecht Wyseur [email protected], NAGRA Kudelski Group, Switzerland

1. Introduction

The initial goal of cryptography has been to design algorithms and protocols to protect a communication channel against eavesdropping. This has been the main activity of modern cryptography in the past 30 years, and resulted in lots of decent ciphers (such as the AES, (T)DES, RSA, ECC) and protocols. In their design considerations, the end points are assumed trusted (black-box) – the attacker only has access to the input/output of the algorithm. For such a model to comply, the algorithm needs to be executed in a secure environment. Active research in this domain includes improved and special purpose ciphers (e.g., lightweight block ciphers, authentication schemes, homomorphic public key algorithms), and the cryptanalysis thereof. From an industrial perspective, the main problem is however the practical deployment. Protocols deployed in the wrong context, badly implemented algorithms, or inappropriate parameters may introduce an entry point for attackers. The deployment of crypto in practice has become a challenge on its own.

The problem even worseness when the black-box attack model does not satisfy any more. In the past 10 years, we have witnessed a lot of new cryptanalysis techniques that incorporate additional side-channel information that can be observed during the execution of a crypto algorithm; information such as execution timing, electromagnetic radiation and power consumption. Mitigating such side channel attacks is a challenge, since it is hard to de-correlate this side-channel information from operations on secret keys. Moreover, the platform often imposes size and performance requirements that make it hard to deploy protection techniques.

Nowadays, we even encounter an even worse attack model, where cryptography is deployed in applications that are executed on open devices (such as PCs or on a tablet/smartphone without exploiting secure elements). We denote this as the white-box attack context. In such a context, a ‘white-box attacker’ has full access to the software implementation of a cryptographic algorithm: the binary is completely visible and alterable by the attacker; and the attacker has full control over the execution platform (CPU calls, memory registers, etc.). Hence, the implementation itself is the sole line of defence.

The challenge that white-box cryptography aims to address is to implement a cryptographic algorithm in software in such a way that cryptographic assets remain secure even when subject to white-box attacks.

Software implementations that resist such white-box attacks are denoted white-box implementations. They are cornerstone in applications were a cryptographic key is involved to protect assets, for example in DRM applications. In such use cases, the software user has an incentive to reverse engineer the application and extract the private key. Similar attacks may occur even when the application user has no incentive – for example when a banking application is executed on a device that is infected by malware or on multi-user systems where other users have elevated privileges. When in such a situation, cryptographic operations are deployed using standard cryptographic libraries such as OpenSSL or cryptographic keys are stored in plain memory, the private key would be unveiled without much effort, no matter how strong the cryptographic primitive used.

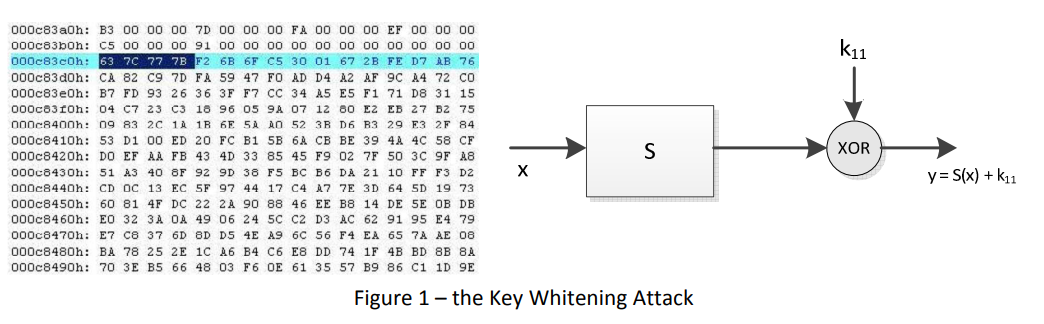

To illustrate such white-box attacks, we present the “Key Whitening Attack” of Kerins and Kursawe [Kerins06]. This attack can be deployed on most AES implementations, including the OpenSSL implementation. Observe that AES deploys a key whitening operation as a final step in its operation; this is an addition with the final round key to protect the final round of the cipher from being annihilated (see Figure 1). The penultimate operation consists of a table lookup operation. Since the design of the cipher is public, the lookup table definition is known; and it is accessible by a white-box attacker. Indeed, with a simple hex editor, these lookup tables can be located in the binary, and changed into zeros. As a consequence, the output of the penultimate operation will result into zero, and hence the execution of the implementation will output the final round key, from which the original AES key can easily be derived.

This article will introduce the broad scope of white-box cryptography. We will introduce the initial white-box implementations that were presented and elaborate on the main cryptanalysis results. The existential questions that were raised as a result (such as existence proofs and boundaries) are addressed in a more theoretic side-track in the research of white-box cryptography; we shall touch this topic only briefly. Finally, we will cover more practical aspects: how white-box implementations are attacked in practice, what kind of additional security mechanisms can be deployed there upon to mitigate practical issues, and what challenges lay ahead.

2. WHITE-BOX CRYPTOGRAPHY

White-box cryptography was first published by Chow et al. [Chow02DES] addressing the case of fixed key white-box DES implementations. The challenge is to hard-code the DES symmetric key in the implementation of the block cipher. The main idea is to embed both the fixed key (in the form of data but also in the form of code) and random data (instantiated at compilation time) in a composition from which it is hard to derive the original key. One of the main design principles in cryptography is the Kerckhoffs’ principle, which states that a cryptosystem should be secure even if everything about the system, except for the key, is public knowledge. White-box cryptography aims to withstand similar public scrutiny: not only does the attacker have full access to the implementation, he also knows which algorithm is implemented and what white-box protection techniques are applied; the security relies on the confidentiality of the secret key and the random data. This stands in contrast to the “security through obscurity” approach that is often conceived with code obfuscation, where one aims to prevent reverse engineering of an application’s code such that an attacker cannot disclose secret algorithms or IP sensitive code.

2.1 WHITE-BOX IMPLEMENTATIONS

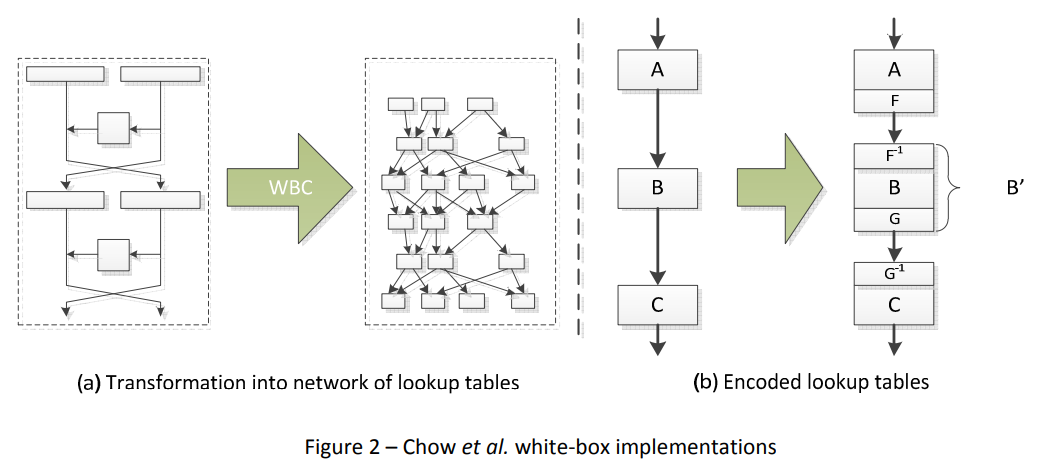

The first white-box implementations were presented by Chow et al. [Chow02DES, Chow02AES] in 2002 on the DES and the AES respectively. Their white-box techniques transform a cipher into a series of key-dependent lookup tables (see Figure 2 (a)). The secret key is hard-coded into the lookup tables and protected by

randomization techniques that are applied. One such method that is deployed is the injection of random annihilating encodings which are merged together with the lookup tables such that the lookup tables and the dataflow in between is randomized, while retaining the overall semantic functionality of the implementation. This is depicted in Figure 2 (b), where F and G are random encodings, which are injected in between A,B and B,C respectively. The overall functionality (input A – output C) remains the same.

The techniques to transform a cipher into a network of lookup tables can easily be extended to other substitution-permutation network (SPN) block ciphers. From a very high level, the steps are as following:

- Re-organize the cipher such that the S-box operations and the operation that includes the round key are adjacent to each other; then hard-code the secret key into the S-box, e.g. Tk(x) = S(x) + k

- Inject annihilating affine operations into the affine block cipher layer. This way, the S-boxes can be re- ordered and the affine operation (usually designed to be as efficient as possible) can be made less sparse. (This is referenced to as introducing ‘mixing bijections’ in the papers by Chow et al.)

- Decompose all the affine operations into a series of lookup tables, thereby even implementing the XOR operation as a lookup table.

- Inject random annihilating encodings into the sequence of lookup tables.

This is a very ad-hoc way of implementing a cryptographic primitive; it is difficult to quantify its security. The only security statement that can be made is “local security”: when B is a bijection and F and G are chosen at random, the B’ does not leak any information. Indeed, given B’, any bijective B with equivalent number of bits as input and output is a candidate since there will always be a pair F,G such that B’ = G.B.F-1. Hence, the attacker is forced to analyse other components of the implementation as well, the aim is that eventually the attacker has to take too many variables into account that would render his attack infeasible. Unfortunately, there are no security proofs that support this statement; in the next section we shall even show how the approach by Chow et al. can be defeated.

Because efficient operations (such as XOR operations) are transformed into lookup tables, there is a large performance and size overhead.

| Implementation | Size | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| WB-AES [Chow02AES] | 770 kBytes | 14.5 kBytes (OpenSSL 1.0) |

| WB-DES [Chow02DES] | 4.5 MBytes | 8.25 kBytes (OpenSSL 1.0) |

| WB-DES [Link05] | 2.3 MBytes |

2.2 WHITE-BOX CRYPTANALYSIS

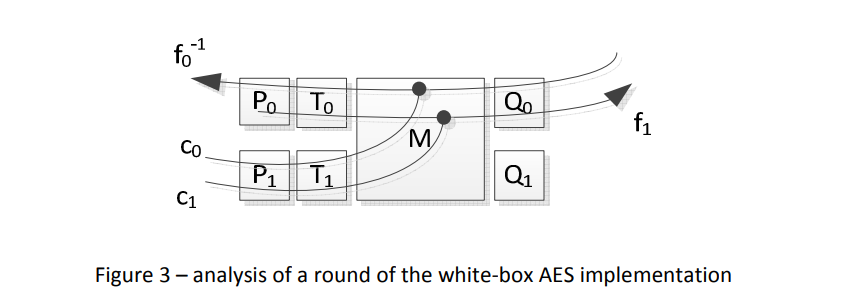

The white-box DES implementation [Chow02DES] was the first that was shown to be insecure. Its vulnerability is mainly due to the DES Feistel structure which can be distinguished in a lookup table representation. The first white-box cryptanalysis techniques find their origin in side-channel attacks such as fault propagation correlation [Jacob02] or guess & determine attacks [Lin05]; however these techniques make some assumptions on the implementation that can easily be mitigated [Link05]. It was only in 2007 that the white- box DES implementation was completely broken with the truncated differential cryptanalysis by Wyseur et al. [Wyseur07] and Goubin et al. [Goubin07]. The white-box AES implementation has been broken by Billet et al. [Billet04] using an algebraic cryptanalysis technique. The presented algebraic technique has shown to be very strong since it directly targets the strategy or randomizing lookup tables. Without entering in too much details, the idea of the attack is as follows:

- Isolate the set of lookup tables that represent one (encoded) round of the underlying AES implementation. Since the transformations that are deployed are known (up to the secret key and the randomness that is introduced), this is straightforward. Figure 3 depicts the composition of such a round, with P and Q internal encodings, Ti are S-boxes with hard-coded keys, and M represents the linear part of the cipher (such as the MixColumns operation).

- Define the functions fi, as bijective functions between a byte at the input of the round and a byte at the output of the round; the inputs to the other bytes are constant but for each fi different.

- Since these fi are bijective and operate on 8-bit, they can easily be inverted and hence composed functions h = f . f -1 can be computed.

- From the set of functions hij, the non-linear component of Q0 can be derived. This is because these functions hij are only dependant on Q0 and the constants ci, cj; they do not depend on P0 and T0.

- Information on Q0 leads to P0 of the next round (since these are annihilating encodings – each other’s inverse). Hence, repeating steps 1—4 over several rounds leads to an AES implementation that is only protected with linear encodings. It is then only a matter of solving the remaining equations to derive the embedded secret key.

Michiels et al. [Mich08] have shown that this algebraic cryptanalysis technique can be deployed on any cipher that has similar properties as the AES (i.e., SPN ciphers with MDS matrices). In fact, they have showed that it are precisely properties that we selected from a black-box security point of view, that made the cipher vulnerable to white-box attacks. In [Wyseur09], we have shown how the algebraic attacks can be used to defeat the whole lookup table based white-box strategy: any lossy lookup table (which are inevitable in lookup table-based white-box implementations) leaks information that can be exploited.

The algebraic cryptanalysis techniques led to the design of new constructions beyond the lookup table strategy, with directions towards implementations with randomized algebraic equations [Bil03] and the introduction of perturbations to defeat the algebraic structure that enables to mount algebraic attacks [Bri06wbc]. The implementation by Billet and Gilbert [Bil03] was broken due to a cryptanalysis result of the underlying primitive that was exploited. Attempts to resolve this issue were inspired by Ding [Ding04] to include perturbation functions to ‘destroy’ the algebraic structure. This led to an improved traceable block cipher scheme [Bri06trace] and was eventually applied to white-box AES implementations [Bri06wbc]. Nevertheless, even these new improved constructions have shown to be insecure by De Mulder et al.[Dem10].

Despite all the new constructions that have been presented, the security of white-box cryptography is very unclear. Almost all of the presented constructions have been shown insecure with academic cryptanalysis papers that have been published. Only a few constructions remain ‘unbroken’, but they are merely a minor tweak to existing constructions – hence the existing attacks will apply with little effort.

Considering the current state of the art in ‘academic’ white-box cryptography, we remain with the following questions:

- Do “strong” white-box implementations exist, and what kind of white-box security is achievable?

- How difficult is it to exploit the attacks in a real-world scenario? We will address these questions in the following sections.

2.3 THEORETIC APPROACHES

White-box cryptography is often linked with code obfuscation, since both aim to protect software implementations. Both have received similar scepticism on its feasibility and lack of theoretic foundations. Theoretic research on code obfuscation gained momentum with the seminal paper of Barak et al. Barak01] who showed that it is impossible to construct a generic obfuscator – i.e. an obfuscator that can protect any given program. Barak et al. constructed a family of functions that cannot be obfuscated; exploiting the fact that software can always be copied preserving its functionality. Nevertheless, this result does not exclude the existence of secure code obfuscators: Wee [Wee05] presented a provably secure obfuscator for a point function, which can be exploited in practice to construct authentication functionalities.

Similar theoretic approaches have been conceived for white-box cryptography in [Sax09]. The main difference between code obfuscation and white-box cryptography is that the security of the latter needs to be validated with respect to security notions. A security notion is a formal description of the security of a cryptographic scheme. For example, a scheme is defined CPA-secure if an attacker cannot compute the plaintext from a given ciphertext, or KR-secure when the secret key cannot be recovered.

It makes sense to define white-box cryptography accordingly since it reflects more reality. Indeed, it does not suffice to only protect an application against extraction of embedded secret keys. For example, to create the equivalent of a smart-card-based AES encryption function in software, it does not suffice that the white-box implementation resists extraction of its embedded key, but it must also be hard to invert. In [Sax09], Saxena and Wyseur have shown that some security notions can never be satisfied in software (IND-CCA2), and they have presented a provably secure construction with respect to the IND-CPA security notion.

The theoretic work showed that white-box cryptography can be seen as a bridge between symmetric cryptography and asymmetric cryptography. A new type of public scheme can be constructed: where the private operation is performed efficiently by a block cipher instantiated with a symmetric key, while the public operation is the white-box implementation of the encryption function with that same symmetric key embedded into its code. Note that this is more challenging to achieve than just protecting the extraction of the secret key. For example, not considering the cryptanalysis results, the original white-box AES implementation can easily be ‘inverted’ since each round can be written as four parallel 32-bit to 32-bit operations; each of them can be inverted easily.

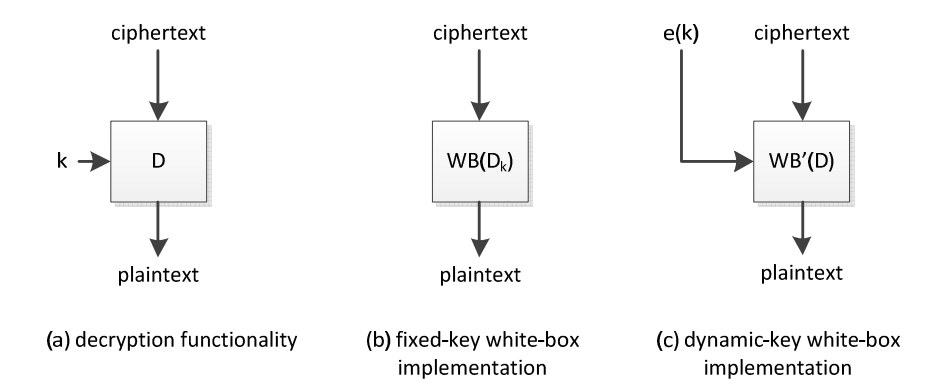

3. WHITE-BOX CRYPTOGRAPHY IN PRACTICE

White-box cryptography is used in several products – companies such as Microsoft, Apple, Irdeto, NAGRA, Sony, Arxan, and many more have announced to deploy white-box techniques, patent technology, and/or have shown to have deployed such technology. Up to now, we have mainly discussed fixed-key white-box implementations, in which the secret key is hard-coded. In practice however, dynamic white-box implementations are more suited. These are implementations that are instantiated with a key only at the time they are called. Of course in such a case, not the original key will be presented (that would lead to an easy disclosure) but a protected version of the key. The dynamic white-box implementation then performs an encryption/decryption operation, by parsing the protection version of the key in such a way that no information on this key is exposed.

The main concerns with white-box cryptography are the performance and size penalty, and its security. The performance issues limit the exploitability of white-box cryptography for high-throughput or constraint use cases such as mobile systems. This can be addressed using special-purpose white-box implementations which can exploit hardware accelerators.

With respect to security: as far as we know, no white-box implementation in a real-world product has suffered from a key recovery attack, despite the cryptanalysis results that have been published. This shows that there is a clear gap between theory and practice, and hence that even ‘weak’ white-box implementations can still serve its purpose up to some extent. To get an idea on how difficult it is to deploy such an attack in practice, we have launched some public challenges on ‘weak’ white-box implementations. They have recently resulted into two independent key recovery results. The conclusion to these attacks is that breaking white-box implementations in practice is a peculiar and very time consuming work. The attacks are very dependent on the construction of the white-box implementation and the properties of the underlying cipher. Hence, widely applicable attacks are difficult to deploy, and there do not exist any automatic tools to break them.

3.1 CODE LIFTING

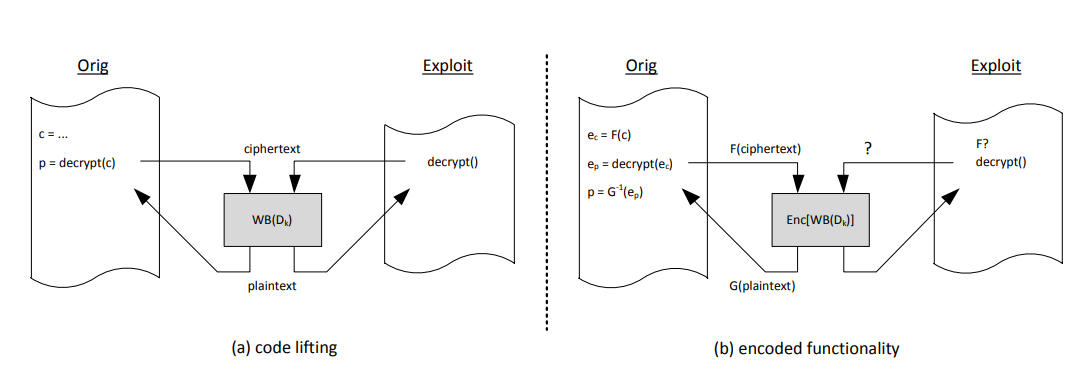

The main issue that white-box implementation suffer in practice is “code lifting”. In such attacks, the attacker will not attempt to extract the secret key from an implementation, but instead use the entire application as if it was a big key. We have seen such attacks in practice several times, where a security library is not being reverse engineered, but instead its decryption functionality is directly called to exploit its functionality.

Code lifting can be mitigated by pushing the white-box implementation’s boundary. This can be achieved by applying external encodings to the original scheme, and including the annihilating encodings at subsequent other places in the containing application; e.g., the annihilating encodings can be incorporated into the function that calls the decryption operation. As a result, the functionality (G . D_k . F-1) is implemented; without knowledge of G and F, the attacker will be unable to use the decryption operation out of its intended context. It will then be up to code obfuscation techniques or process isolation into a secure environment to ensure that these functions G and F cannot be extracted from the call function. Consequently, we also have a method to associate a cryptographic operation to a secure component; we can do node-locking. This is an example of preventive software protection techniques.

3.2 SOFTWARE FINGERPRINTING

Another direction is to deploy reactive strategies: be able to detect who has been sharing code (with an embedded key). In [Mich07], Michiels and Gorissen presented a technique to insert fingerprints into white-box implementations. The main idea is the observation that the internal annihilating encodings can be chosen as such that the resulting final lookup tables contain an arbitrary predefined value. This value can be a fingerprint that can be used to identify the software or introduce a copyright onto cryptographic keys. The same approach can also be used to enable a form of software tamper resistance: when the resulting lookup tables contain values that represent bytecode or assembly instructions, any modification of this representation may lead to a modification of the white-box lookup tables and hence render the functionality of the underlying cipher obsolete. Hence, the software has a dual representation. The security of this approach is questionable however – first of all, it depends on the security of the white-box implementations, which is already questionable – secondly, such an approach can easily be defeated since the attacker can insert additional internal encodings which destroys the fingerprint, he can deploy a cloning attack that distinguishes the execution of the code from the execution of the underlying white-box implementation.

A stronger reactive strategy has been presented by Billet and Gilbert [Bil03] who made a white-box implementation that is inherently traceable. That is, they presented a new block cipher construction, from which several instances can be generated; each instance is functionally equivalent, but under inspection of its code identifiable. Unfortunately, the basic building block upon which this block cipher was constructed has been defeated. Based on the idea of introducing perturbations, Bringer et al. [Bri06trace] reinforced the traceable block cipher.

4. CONCLUSION

White-box cryptography is a necessary building block in any sane overall software security strategy – it is cornerstone in the protection of cryptographic primitives in applications that run on hostile execution platforms. The initial white-box techniques have been presented in 2002, with implementations of the DES and

AES ciphers. Since then, white-box cryptography has gained momentum: we have witnessed several cryptanalysis results and new constructions; and theoretic foundations have been formulated. These days, white-box cryptography is being used in real-world applications; mainly DRM applications. While academic attacks have been published, as far as we know, no attacks on commercial white-box implementations have been seen. Instead, attackers focus on other parts of the system and exploit the cryptographic functionality without attacking it. Nevertheless, white-box cryptography provides opportunities to battle on that front: code lifting attacks can be mitigated by locking the white-box implementations into the application; and other security features such as traceability can be mounted upon white-box implementations.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The original version of this article has been written in English, and can be retrieved at www.whiteboxcrypto.com. We would like to thank Jean-Bernard Fischer for his effort to translate this article into French.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

| Mark | Desc. |

|---|---|

| [Barak01] | Boaz Barak, Oded Goldreich, Rusell Impagliazzo, Steven Rudich, Amit Sahai, Salil Vadhan, and Ke Yang. On the (Im)possibility of Obfuscating Programs. In Advances in Cryptology - CRYPTO 2001, volume 2139 of Lecture Notes in Computer Science, pages 1–18. Springer-Verlag, 2001. |

| [Bil03] | Olivier Billet and Henri Gilbert. A Traceable Block Cipher. In Advances in Cryptology - ASIACRYPT 2003, volume 2894 of Lecture Notes in Computer Science, pages 331–346. Springer- Verlag, 2003. |

| [Bil04] | Olivier Billet, Henri Gilbert, and Charaf Ech-Chatbi. Cryptanalysis of a White Box AES Implementation. In Proceedings of the 11th International Workshop on Selected Areas in Cryptography (SAC 2004), volume 3357 of Lecture Notes in Computer Science, pages 227–240. Springer-Verlag, 2004. |

| [Bri06trace] | Julien Bringer, Herv´e Chabanne, and Emmanuelle Dottax. Perturbing and Protecting a Traceable Block Cipher. In Proceedings of the 10th Communications and Multimedia Security (CMS 2006), volume 4237 of Lecture Notes in Computer Science, pages 109–119. Springer- Verlag, 2006. |

| [Bri06wbc] | Julien Bringer, Herve Chabanne, and Emmanuelle Dottax. White box cryptography: Another attempt. Cryptology ePrint Archive, Report 2006/468, 2006. |

| [Chow02DES] | Stanley Chow, Philip A. Eisen, Harold Johnson, and Paul C. van Oorschot. A white-box DES implementation for DRM applications. In Proceedings of the ACM Workshop on Security and Privacy in Digital Rights Management (DRM 2002), volume 2696 of Lecture Notes in Computer Science, pages 1–15. Springer, 2002. |

| [Chow02AES] | Stanley Chow, Philip A. Eisen, Harold Johnson, and Paul C. van Oorschot. White-Box Cryptography and an AES Implementation. In Proceedings of the 9th International Workshop on Selected Areas in Cryptography (SAC 2002), volume 2595 of Lecture Notes in Computer Science, pages 250–270. Springer, 2002. |

| [Dem10] | Yoni De Mulder, Brecht Wyseur, and Bart Preneel, “Cryptanalysis of a Perturbated White-box AES Implementation,” In Progress in Cryptology - INDOCRYPT 2010,Lecture Notes in Computer Science 6498, K. Chand Gupta, and G. Gong (eds.), Springer-Verlag, pp. 292-310, 2010. |

| [Ding04] | Jintai Ding. A New Variant of the Matsumoto-Imai Cryptosystem through Perturbation. In Proceedings of the 7th International Workshop on Theory and Practice in Public Key Cryptography (PKC 2004), volume 2947 of Lecture Notes in Computer Science, pages 305–318. Springer-Verlag, 2004. |

| [Goubin07] | Louis Goubin, Jean-Michel Masereel, and Micha¨el Quisquater. Cryptanalysis of White Box DES Implementations. In Proceedings of the 14th International Workshop on Selected Areas in Cryptography (SAC 2007), volume 4876 of Lecture Notes in Computer Science, pages 278–295. Springer-Verlag, 2007. |

| [Jacob02] | Matthias Jacob, Dan Boneh, and Edward W. Felten. Attacking an Obfuscated Cipher by Injecting Faults. In Proceedings of the ACM Workshop on Security and Privacy in Digital Rights Management (DRM 2002), volume 2696 of Lecture Notes in Computer Science, pages 16–31. Springer, 2002. |

| [Kerins06] | Tim Kerins and Klaus Kursawe. A cautionary note on weak implementations of block ciphers. In 1st Benelux Workshop on Information and System Security (WISSec 2006), page 12, Antwerp, BE, 2006. |

| [Link05] | Hamilton E. Link and William D. Neumann. Clarifying Obfuscation: Improving the Security of White-Box DES. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Information Technology: Coding and Computing (ITCC 2005), volume 1, pages 679–684, Washington, DC, USA, 2005. IEEE Computer Society. |

| [Mich07] | Wil Michiels and Paul Gorissen. Mechanism for software tamper resistance: an application of white-box cryptography. In Proceedings of 7th ACM Workshop on Digital Rights Management (DRM 2007), pages 82–89. ACM Press, 2007. |

| [Mich08] | Wil Michiels, Paul Gorissen, and Henk D.L. Hollmann. Cryptanalysis of a Generic Class of White- Box Implementations. In Proceedings of the 15th International Workshop on Selected Areas in Cryptography (SAC 2008), Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Springer-Verlag, 2008. |

| [Sax09] | A. Saxena, Brecht Wyseur, and Bart. Preneel, “Towards Security Notions for White-Box Cryptography,” In Information Security - 12th International Conference, ISC 2009, Lecture Notes in Computer Science 5735, C. A. Ardagna, F. Martinelli, P. Samarati, and M. Yung (eds.), Springer-Verlag, 10 pages, 2009. |

| [Wee05] | Hoeteck Wee. On Obfuscating Point Functions. In Proceedings of the 37th ACM Symposium on Theory of Computing (STOC 2005), pages 523–532, New York, NY, USA, 2005. ACM Press. |

| [Wyseur07] | Brecht Wyseur, Wil Michiels, Paul Gorissen, and Bart Preneel. Cryptanalysis of White-Box DES Implementations with Arbitrary External Encodings. In Proceedings of the 14th International Workshop on Selected Areas in Cryptography (SAC 2007), volume 4876 of Lecture Notes in Computer Science, pages 264–277. Springer-Verlag, 2007. |

| [Wyseur09] | Brecht Wyseur, “White-Box Cryptography,” PhD thesis, Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, Bart Preneel (promotor), 169+32 pages, 2009. |